Draghi tries again to save the euro

2024-09-27

BY CHELTON WEALTH

Draghi tries again to save the euro

In 2012, Draghi compared the euro to a bumblebee. Aerodynamically, a bumblebee should not be able to fly, but it succeeds by some mystery in nature. This speech contained two sentences that ensured Draghi would go down in history as the saviour of the euro: ‘Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.’ The ECB will ‘do whatever it takes’ to save the euro. Now, the ECB’s pockets are theoretically infinitely deep, so the market knew immediately that there was no longer any point in speculating against the euro. This did not solve the problem but brought time for a political solution.

Divergent euro

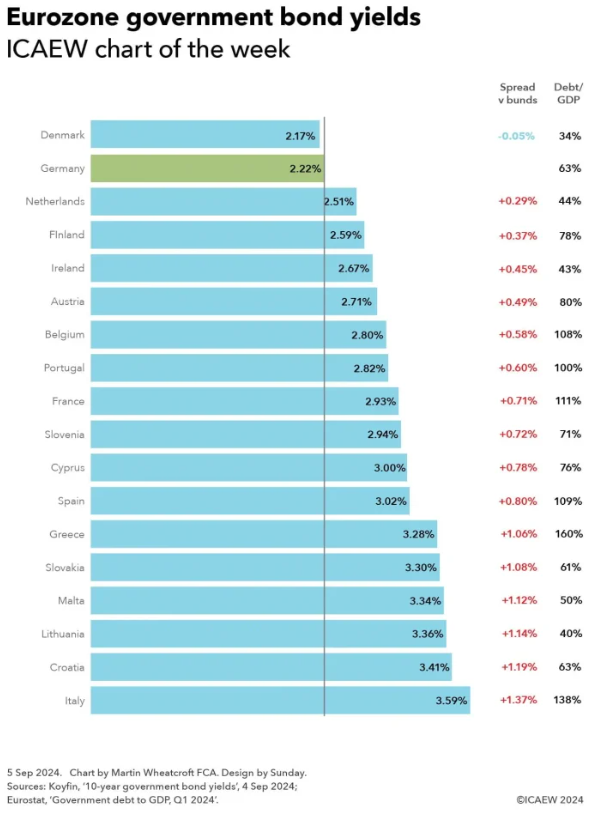

The euro is a diverging system. The large differences within the eurozone combined with a single shared currency make those differences larger rather than smaller. The Maastricht Treaty aimed to reduce those differences, but it failed hopelessly. After the Great Financial Crisis, Germany tried to germanise the rest of Europe, but that too proved anything but the right solution. Europe’s strength lies precisely in diversity, not uniformity. The eurozone (a consequence of German reunification) is not finished either. There may be a monetary and banking union, but not yet a capital market union or fiscal union.

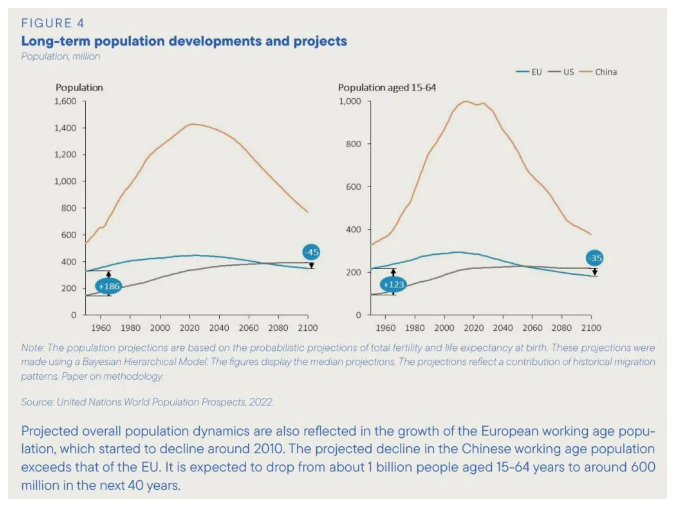

European growth is more than the eurozone

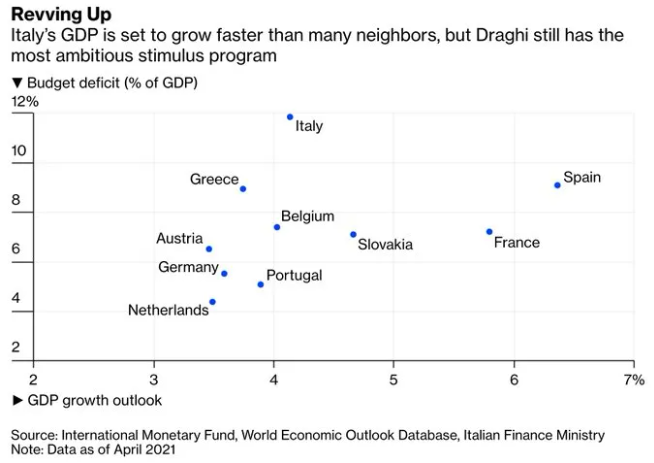

According to Draghi, Europe is lagging behind China and the United States. That is not so bad if you also look outside the eurozone. The former Eastern bloc (including the former East Germany) has experienced spectacular growth since the wall's fall. The difference between the United States and the US is its deliberate immigration policy. If an immigrant leaves and starts a successful business outside the US, US politicians see this as a failed immigration policy. Those immigrants have provided extra economic growth in the US. Draghi points out that increased regulation in Europe is depressing growth, but that is true of all times.

Southern European solutions

Draghi misses the point because he thinks state aid and industrial policy can make Europe grow faster again. Draghi wants productivity to grow but puts too much responsibility on the government—exactly the part of the economy not precisely known for productivity growth right now. Furthermore, Draghi is trying to perfect the eurozone further. This requires, among other things, a shared capital market and more fiscal power to Brussels. Thanks to the pandemic, there is already a 750bn stimulus package (much of which goes to Italy) funded by Eurobonds (conveniently called coronabonds ). This 800 billion (per year) will come on top of that, although some will also have to come from the private sector.

Decarbonisation

At the heart of Draghi’s plan is an acceleration of the energy transition. The problem is that Europe is going backwards rather than forwards in competitiveness. Currently, fossil energy is already much more expensive in Europe than in the rest of the world. The rest of the world, especially in emerging markets, often sees the energy transition as a luxury problem they cannot afford. Energy security is much more important. European companies that do go green will demand a level playing field, which is only possible with import tariffs that will, in turn, be followed by countermeasures against European products. The only solution to accelerate the energy transition is through technological breakthroughs that will make alternative energy structurally cheaper than fossil fuels. Even then, this will not be completed within a few years but rather several decades. It has taken us more than 150 years to extract and burn more than 100 million barrels of oil daily (and we are still on record demand for oil). This will be a long and arduous transition.

Eurobonds

Transferring more financial power to Brussels is against the very leg of northern member states. That is why Draghi used the term Eurobonds in the voluminous report. Yet Draghi has such a strong reputation that in the next euro crisis (things are currently not going well in Germany and, if possible, even worse in France), Draghi’s plan is likely to be the only plan to save the euro again. Europe is used to reforming in times of crisis anyway, preferably just after the last deadline has expired. An annual capital injection of 800 billion may not be economically efficient, but it will likely provide a short-term boost that benefits financial markets.

Abolishing the euro

A better solution for Europe to grow economically is to abolish the euro. Countries that are part of Europe but not part of the eurozone grow as much or, if possible, more strongly than euro countries. No Swiss company is complaining about the Swiss franc and the lack of the euro. Especially now that all payments are digital, the euro is nothing more than a unit of account for business. The end of the euro also means the end of the European Union in its current form. However, this is offset by a potentially much larger European alliance. With the UK, Switzerland and Norway, such a new European alliance would double the current Union's economic potential. That means much greater clout towards China and the US, countries with which it would be better to negotiate a ‘level playing field’ than to start a trade war on import tariffs to trigger a recession.

Conclusion

Draghi’s plan has many shortcomings, but in the current balance of power, that does not mean it will not be implemented. In the next euro crisis, there will not be so many alternatives. Indirectly, Draghi is trying to perfect the eurozone with the plan, which means there will be no turning back soon. However, this means that the national member states must be willing to transfer a greater part of their power to Brussels, which would require a solid euro crisis.