Japanese intervention

2024-06-03

BY CHELTON WEALTH

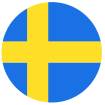

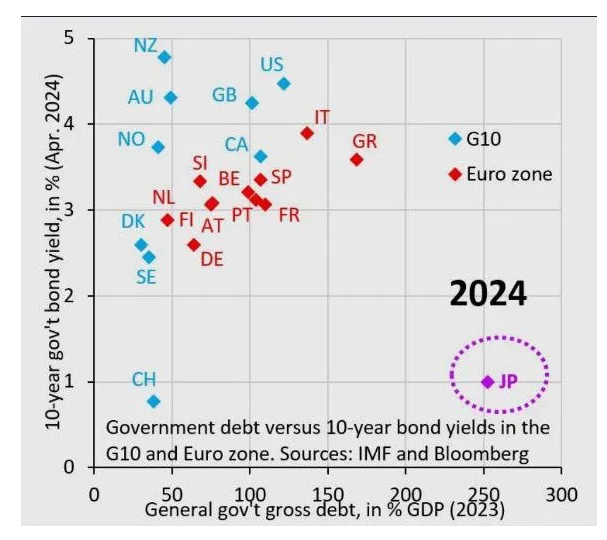

Inflation is back in Japan, structurally ensuring higher nominal growth averaging 2.5 per cent of GDP. A 10-year interest rate of 1 per cent also ensures that government debt can shrink as a percentage of GDP. Inflation also increases efficiency in capital markets and returns dynamism to Japan's corporate sector. Investors face rising profitability and still low valuations.

Structurally higher earnings and still cheap

Japanese equities will achieve a return on equity of 12 per cent next year, three times higher than at the start of Abenomics in 2012. That higher profitability will ensure that Japanese equities are valued higher. Japanese equities are still cheap in several ways. Moreover, Abenomics has succeeded in ending the decades-long flirtation with deflation. There is again a positive wage-price spiral in Japan. Inflation is high enough to encourage consumers to spend more but not so high that the central bank will raise interest rates sharply. Also important for investors is the improved governance in recent years. Corporate management is more mindful of shareholders.

Weak yen

Much of the positive development in the Japanese stock market has been lost due to the weak yen. This could be avoided by hedging the Japanese yen to the euro, but this is not wise in the long term. Firstly, the Japanese yen is severely undervalued. In addition, the Japanese yen typically strengthens in times of stress. It thus performs a similar safe haven role to the US dollar. This is because Japanese investors repatriate their foreign exposures during market stress. That effect is weaker than before but still present. Moreover, there are always two sides to currency movements, and in that context, it makes sense to hold as little as possible in euros.

Intervention in currency markets

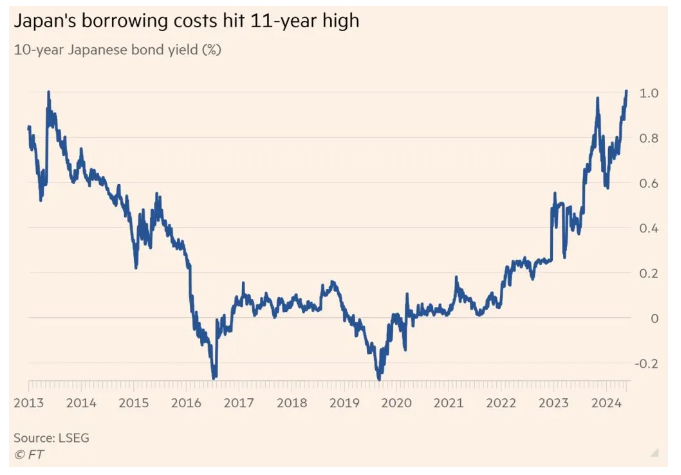

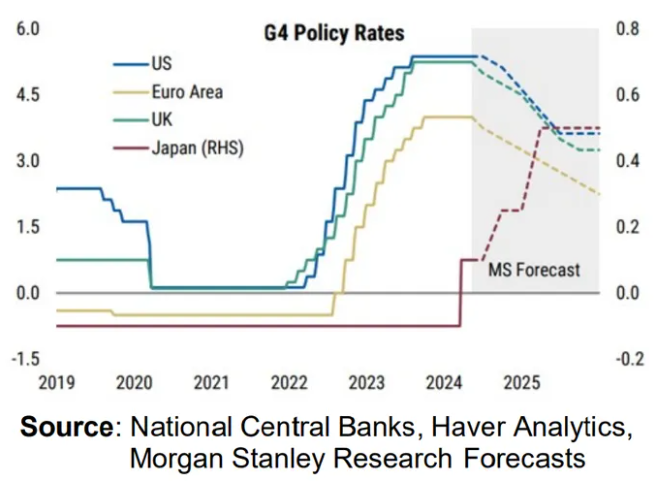

The Japanese government has supported the Japanese currency in recent weeks. The Japanese government has intervened in the currency market no less than 13 times since 1990, but usually with only short-term results. Yet, this time, the intervention takes a little longer to take hold. There are several reasons for this. Japan has recently deployed around $60 billion to support the yen. The country still has $1.3 trillion in foreign exchange reserves. With this intervention, Japan achieves higher volatility, which may cause fewer carry trades (financed in yen) to be set up. Better than intervening in the foreign exchange markets is to ensure that interest rate differentials with, say, the United States decrease. The Bank of Japan will likely raise interest rates again this year, and a Federal Reserve rate cut is still expected.

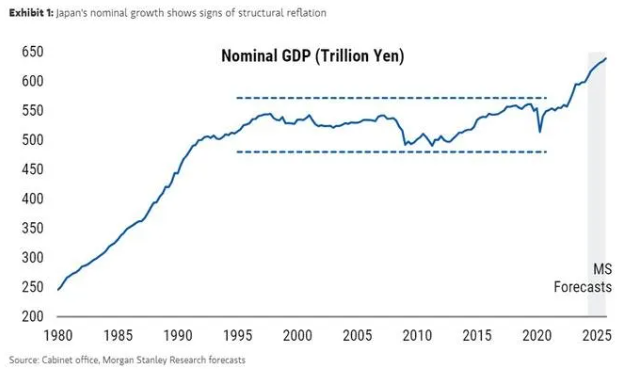

Getting institutions to invest more in Japan

A relatively simple way to ensure a stronger yen is to impose rules on institutions on how much they can invest outside Japan. Now these institutes have an amount outstanding outside Japan equal to 80 per cent of Japan's GDP. Because of the weak yen, large profits have been made on these exposures, which is an excellent time to repatriate some of that money. That could start happening when the GPIF (Japan's largest fund) adjusts its 25 per cent allocation to Japan (60 per cent 10 years ago). This will be followed almost immediately by many other institutions. With $1.5 trillion in assets, the GPIF has much impact. The GPIF has a long-term yield forecast of 0.7 per cent on Japanese bonds, but recently, interest rates in Japan rose to 1.0 per cent, the highest point in 11 years.

Exports, competition with China and Germany

Japanese businesses also benefit from a weak yen (via exports), but much has been done in recent decades to reduce this sensitivity. For instance, many components for Japanese products are also produced in other parts of Asia. Furthermore, the yen is mainly weak to compete with the other undervalued Asian currency, the renminbi. For exports, China is now more important than the United States. A weak yen also makes for excellent competitiveness against, say, Germany. Both countries have much overlap in exports, such as cars and capital goods.

Yen makes everything cheap

Due to the weak Japanese yen, everything in Japan is still extremely cheap. Japan is increasingly an alternative for those looking for a holiday where everything is value for money. The Japanese government has to balance economic and monetary policy with the yen. The financial benefits of a weak yen are obvious, and monetarily, a weak yen creates more inflation. Inflation is still not the problem (but rather a solution in Japan's case), but there will come a time when interest rate differentials with the rest of the world start to narrow. The Japanese government has more options besides intervening in the currency markets, so this could make for a more credible policy towards the yen.