The Policy Changes of the Bank of Japan

2024-03-28

BY CHELTON WEALTH

Last week, the Bank of Japan was the latest central bank to end its policy of negative interest rates. The move was small, from a policy rate of -0.1 per cent to a rate of 0.1 per cent. Then, the Swiss rate cut of 0.25 per cent was more significant. However, the Bank of Japan is also stopping it from regulating long-term interest rates, though it is not accepting a rapid rise in them. Furthermore, the Bank of Japan no longer buys equities (ETFs and REITs). Since the end of 2022, the end of this policy was already expected, but the Bank of Japan has taken its time and remains cautious. At the same time, the central bank has found enough confirmation in the latest wage rounds (+5.3 per cent, the highest wage growth in 33 years) that the years-long flirtation with deflation is over.

The ZIRP policy

The Bank of Japan was not the first central bank with negative interest rates. The ECB preceded Japan, and Sweden and Denmark were ahead of it again. Japan did have zero interest rates (Zero Interest Rate Policy or ZIRP) for a long time before that. Japan seemed a unique case for a long time until several central banks cut interest rates to zero per cent. We all started to look a bit like Japan. Japan was also the first central bank to experiment with quantitative easing, buying up bonds and, in Japan’s case, equities. Japan even went a bit further as it committed to price (quality) rather than quantity (quantity), a policy known as Yield Curve Control (YCC). By committing to a price, the Bank of Japan had to buy up unlimited quantities in theory, although, in practice, it was not that bad. The market did some of the work for the central bank.

End of the carry trade

Because Japanese monetary policy was very loose for a long time, many Japanese investors financed their foreign investments with yen. Through these so-called carry trades, the Japanese made a lot of money. Not only did holdings abroad yield more than the cost of financing, but at the same time, the yen weakened. It made the Japanese yen a safe haven for investors for a long time. Japanese investors repatriated their foreign investments during a crisis, causing the yen to rise sharply. So, that hedge is weakening, although the shift from -0.1 to 0.1 per cent is not large. It has also become less attractive to keep setting up such carry trades.

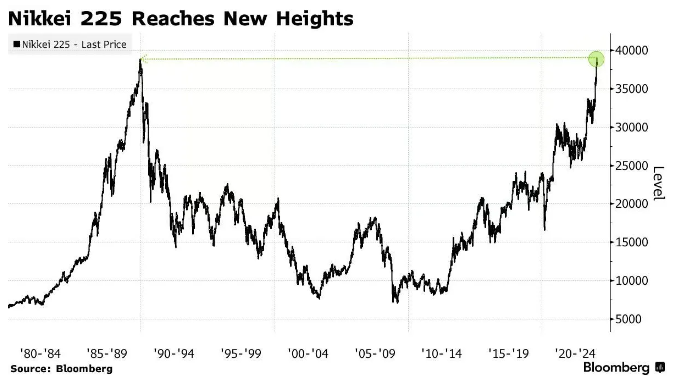

Flight towards the stock market

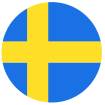

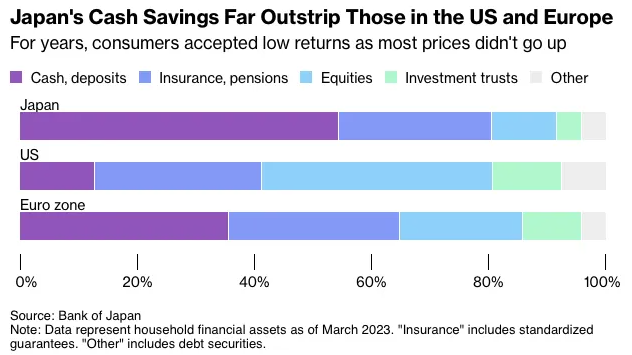

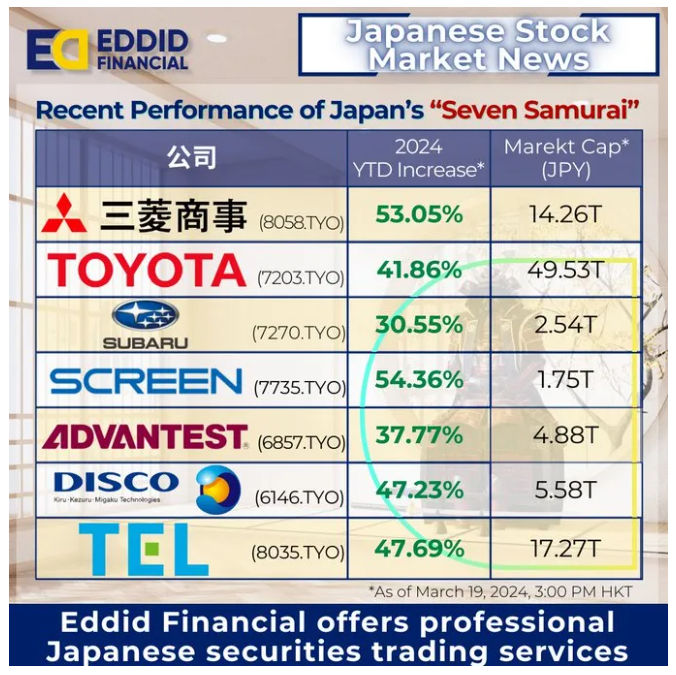

The alternative is for Japanese (individuals and institutions) to invest more in Japanese equities. This is supported by the fact that inflation has risen in Japan. The weak yen is driving solid results from Japanese exporting companies, rapidly gaining market share from Germany. The tilt in sentiment towards equities is confirmed by the fact that the Nikkei is above 40,000 points for the first time, ending its long correction since 1989. Meanwhile, Japan also has an acronym for the stock market. Whereas the US stock market has been given the narrative of the Magnificent Seven and Europe has to make do with the Granolas, it is the Seven Samurai in Japan.

At the same time, Abenomics-inspired reforms are generating increasing interest from foreign investors. These were looking for an alternative to Chinese equities in Asia anyway. The fact that both domestic and foreign investors are buying Japanese equities is fairly unique; thus, there still seems to be plenty of upside. On top of that, the potential for earnings improvement in Japan is enormous. Japanese listed companies have no net debt and plenty of limited profitable activities to divest or otherwise optimise. Japan is very attractive to private equity for this reason.

Stronger yen over time

The interest rate hike in Japan is counter to the upcoming rate cut in the US and Europe. However, the recent rate hike was small. As interest rate differentials narrow, the current weakness in the yen is no longer justifiable. At the same time, the weak yen ensures that Japanese companies can do good business in, for example, China, Japan’s most important export country.